1 Introduction

In one of the recent TrustDefender Labs reports (“Man-in-the-Browser 101 or it works as designed (Win & Apple Mac) – http://www.trustdefender.com/trustdefender-labs-blog-td-labs-blog-man-in-the-browser-101-or-it-works-as-designed-win-aamp-apple-mac.html) we gave a brief over-view of what a Man In The Browser attack was all about, and in that discussion we briefly touched on Man In The Browser (MITB) attacks on Mac OS X. But is this really plausible?

The reputation for Apple’s OS has been that its more secure and doesn’t suffer these problems. Well, we have touched on, and debunked this myth earlier, but the malware examples we have looked at have all been pretty unsophisticated. So maybe there is something in this idea of a more secure OS? Well, given the title of this article, you can guess that’s not true!

We will be looking at three different ways that MITB can be achieved on Mac OS X as well. The most interesting fact is that it is actually fairly easy to do and works exactly the same way as on Windows. Given the detailed knowledge of MITB from the fraudsters on Windows, one can only assume that they have the knowledge as well on Mac and it is only a matter of time before they maintain two complete different versions of their trojan, perhaps with a shared configuration.

2 Browser Hooking

In the previous article, we talked about function hooking, and, although that article was focused on Windows, the concept is exactly the same for Apple OS’es. The basic idea is simple. When the web browser calls a system function, we re-route the call to execute our code first.

We have identified three different methods for getting our code to be called before a system function is called. This list is not exhaustive by any means, and we will cover each in turn in a later in-depth report, but the point is there are multiple ways of achieving this goal.

Specifically,

- Library overloading using DYLD_LIBRARY_PATH

- Function overloading using DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES

- Code injection

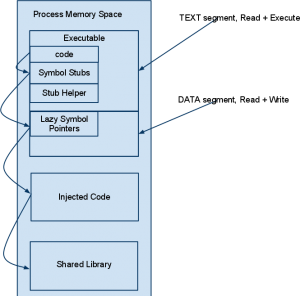

The first two of these use features made available by the dynamic linker, and the last is a more complicated method where we inject some code directly into another processes memory. However, regardless of which of method is used, they all rely on the same basic idea. Rather than directly calling a system function, we first call our function first. Like this:

We will cover lazy linking, and explore in more detail the details this image shows in a later article. For now, its enough to know that the system used to resolve symbols in shared libraries, can be perverted and used to call our code instead. All three of the mentioned methods exploit this mechanism, albeit in slightly different ways. Typically, in this situation, the injected code will do its thing, and then call the original system code, so the system call still does what it needs to for the process to run (at least apparently) correctly.

2.1 Results

So, now we get to the interesting part! We have the pieces in place, we just need to figure out the appropriate places to hook, and inject our code. The details of this aren’t really important here, but suffice to say its not a big issue to figure these things out. For MITB malware, we need to find a function that is called to retrieve network traffic, ie our HTML content, from the network. And, if we hook at the right place, we can get access to html content before its encrypted and sent, and also after its received and decrypted. This means that SSL doesn’t help protect the content. We can then add whatever content we like… and we can do all this with no special access rights!

This sounds very familiar from all the MITB trojans on windows such as Zeus, Spyeye, Carberp, Gozi, Mebroot,… And yes, exactly the same thing is easily doable on Apple Mac OSX as well.

So how does it look like?

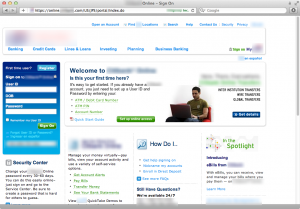

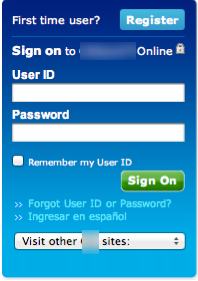

Note the https url, the lock symbol indicating a secure session… and the extra form field in the sign on section. In case you aren’t familiar with citibank’s sign on page, the relevant section of the same site without our hook looks like this:

Note that we picked citibank for this exercise simply because they are a well known bank. There is no inherent flaw in their website (that we know of, anyway), its a fairly typical banking site, secured with SSL and a certificate from a trustworthy CA (whatever that means in these days!).

Its also worth noting that the code required to inject an extra form element into the page was of medium complexity and highly targeted to this particular website. This was mentioned in an earlier article that suggests the meaningful Intellectual Property is in the configuration file rather than the code injection method. All major MITB trojans share the same “Zeus style” web-inject configuration format to target many brands at the same time. This is where the real value of a MITB lies, and given its brand-specific, is no tied to the delivery platform at all.

All three methods outlined in this report will result in the same compromised page where 99% of the content comes from citibank, but some additional form fields or malicious JavaScript fragements are injected locally – even though EV-SSL is used and the padlock is visible.

The above results are possible using all three methods.

2.2 What next?

Over the next few articles we will look in greater detail at the 3 methods of hooking mentioned above. We will also touch on the security features available in Mac OS X (10.6 and 10.7) and how effective they are for this kind of attack.